I love motels.

In my adult life, I’ve finally graduated to an income bracket that allows me to upgrade my lodging options so I could, if I wanted, hole up in fancier digs, with niceties like a pool, all-you-can-eat breakfast, as many pillows as one feels comfortable requesting, and the holy-of-holies, a hot tub next to the pool, but my heart still stops for these old roadside resting places.

I’m on an annual mission, driving three hundred miles to perform for free for twenty minutes at an electronic music festival for an audience of fifteen to twenty people who are mostly the other musicians from the festival, and the drive this time was wearing, with a hour spent navigating the crawling traffic piled up behind a highway accident that the supposedly intelligent machinery behind the map application on my mobile device utterly failed to route me around (in the end, I engineered my own detour and saved a good forty-five minutes). So, despite leaving on time, I lumbered through the swooping byways through Pennsylvania mountains, alerted frequently to watch for deer by signs with a stylized jumping buck over a farcical number of miles that was computed…how, exactly?

I paused at a rest stop where a machine would dispense, for my utility, a gritty horror it labeled a “capuccino” (my options on the machine, announced after I’d paid, as instant or decaf) to me, which I managed to spill all over myself, but I credit it with enough caffeine to keep me alert and alive for the last hour and change where the road fatigue was properly kicking in. I listened to the remainder of the familiar radio drama that had kept me company for a couple hundred miles, and in the last moments, as the credits played, I pulled up into the forecourt of the old motel, laid out in the midcentury style, with a little office at the center of two low, sweeping wings of rooms, each door facing its own parking spot, parked, and and staggered into the office with all my road cramps in concert.

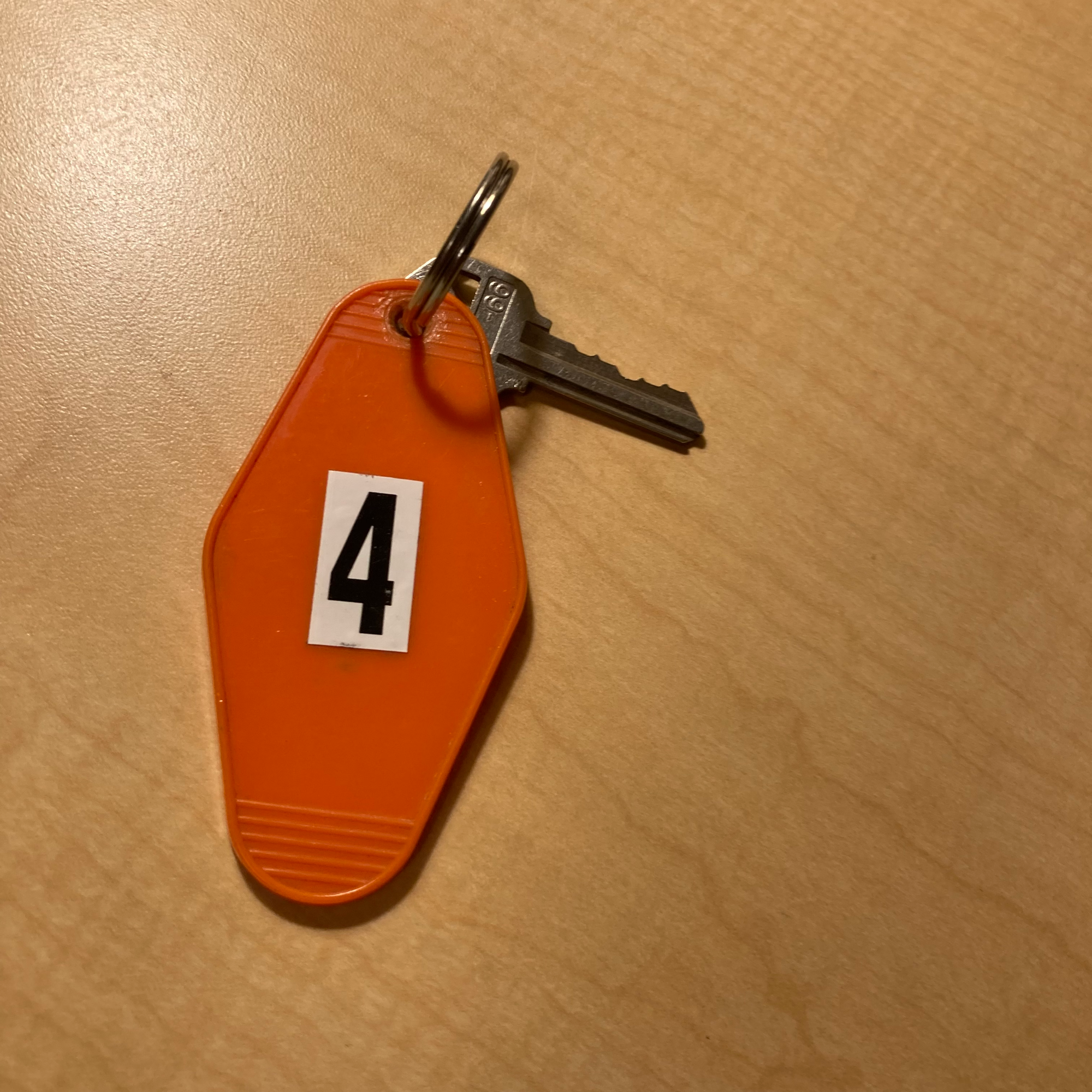

The office smelled of cabbage, which was made all the more clear by the presence of a large glass-fronted refrigerator filled halfway with those large, oblong cabbages you find in an Asian grocery store, and the rustling from the back room announced the hunched older gentleman who shuffled in and quietly answered as I indicated I’d booked and paid online. He had me present my ID, fill out a card with my relevant information, and sign the card and receipt for the four nights I’ll be here, and handed over what I was delighted to find was a proper old-fashioned motel room key on an oversized orange fob, and I headed back to the car to move to the slot in front of room #4.

In cheap motels, one always opens the door for the first time with a little hesitancy, a lottery not enjoyed by my husband, who prefers the dependable security of a room with no potential for surprises, as there will sometimes be a bilious cloud of aging cigarette stink even for a room officially marked as non-smoking, or the scent of mold, mildew, or sewer issues, but this one was a reminder.

I took a deep breath and it was all 1978, that sort of vaguely musty smell of settled air and linens freshly washed a couple weeks prior, and I was happy.

The room is vintage in all the ways I prefer, with old, but not rickety, furniture, painted-over paneling, and a bathroom that is functional and tightly screwed together, and if not for the flat television, the composite flooring in lieu of linoleum or the horror of ancient wall-to-wall carpet, and the spotted lanternfly flitting around the room it might as well be on of the motels I stayed in in my first ventures with a car, nearly forty years ago.

It is a nostalgic moment and I am comfortable with that, with a nice place to stop and stay for a while that brings back family trips in our enormous silver and purple Chevrolet Suburban, where we’d book in late on the road to Georgia, get a big room with a cot, turn the AC up, and turn on the TV, and I’d be home there, in a place that, for the moment, I could pretend was the world I actually lived in.

I love that feeling of settling in, even if I’m only staying in a place for a night, where I put my bags in the drawers in the dresser and line everything up neatly as if I intended to put down roots and live there forever, or just for a brief interval before moving on like a seasoned traveler of the world.

The bed is comfortable, the toilet is bolted firmly to the floor and the seat isn’t loose—the giveaway sign of an innkeeper that has graduated from caring about their work—and the water doesn’t stink of sulfur or fish. The toilet flushes with a peculiar symphony of clicks, hisses, and, at the end of the cycle, a combination of a bell-like sound and a last gloomph, and I am comfortable with that and the sound of the wall-mounted AC fan and the nearby interstate churning away like a fine work of the drone musician’s art. The side street traffic rises and falls, punctuated by the rumbling of trucks, and I note, looking out of the little bathroom window as I’m brushing my teeth and shaking a handful of pills out of the TH slot in my pill minder, that my room backs up to the scenery of a auto repair shop and a camper trailer rental lot. I spit, rinse the sink, slug down four tablets, and switch off the light.

It is just a place that isn’t really a place. I’ll be here for four nights, then leave, and it’s statistically unlikely I’ll ever be in this room again for the remainder of my life, but that doesn’t trouble me like it used to back in 1978, when I was ten and things and places had a life for me like the spirits in animist religions, where every object and place was haunted by little ghosts that I’d only just met, and then had to leave behind. I used to feel a terrible sadness when we’d pack up, load the Suburban, and leave, wanting to gently touch the walls and whisper “Goodbye,” and “You were a very good motel room” before continuing on the family travels, but pragmatism and a long-running pattern of loss makes it easier and easier to say goodbye to such things.

In the interim, this is my home away, at the industrial edge of a Northern town that’s showing its age and its own losses, and between my time spent with others on my same wavelength, I’ll hole up here, organizing the room as if it’s mine, and then head out again, on the trip with a destination that’s not as far away as it used to be, and that is as things always are.

© 2025 Joe Belknap Wall