A recent exchange reminded me of a great book I read recently, as an attempt to rediscover the love of science fiction I’d once had, and which had faded with the devolution of sci-fi into bleak pessimism, a perverted wallowing in the supposed hopelessness in our species, diseased and fetishistic lusting for (and after) the apocalypse as a sort of displaced modernization of the religious sickness of the flagellant, and war war war war war war war and every narrative turning on the gun, because people can’t be bothered to read Ursula K. Le Guin’s elegant counter in the brief, but insightful, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.”

I’d gone so far as to attempting my own sci-fi novel as a nod to James Murphy’s excellent dictum that the best way to complain is to make things, setting some basic rules—no war, no AI, no FTL travel, no artificial gravity, no murders…and so on—writing at a leisurely pace that equates to “I wonder if I’ll finish this before I die,” but along the way, helpful fans in my circle pointed out some excellent humane modern science fiction of a genre that’s been dubbed “solarpunk,” which inspired me to wonder if I could catch the tail of that flowing gown as its practitioners stride into a future that’s not the usual grimdark catalog of miseries.

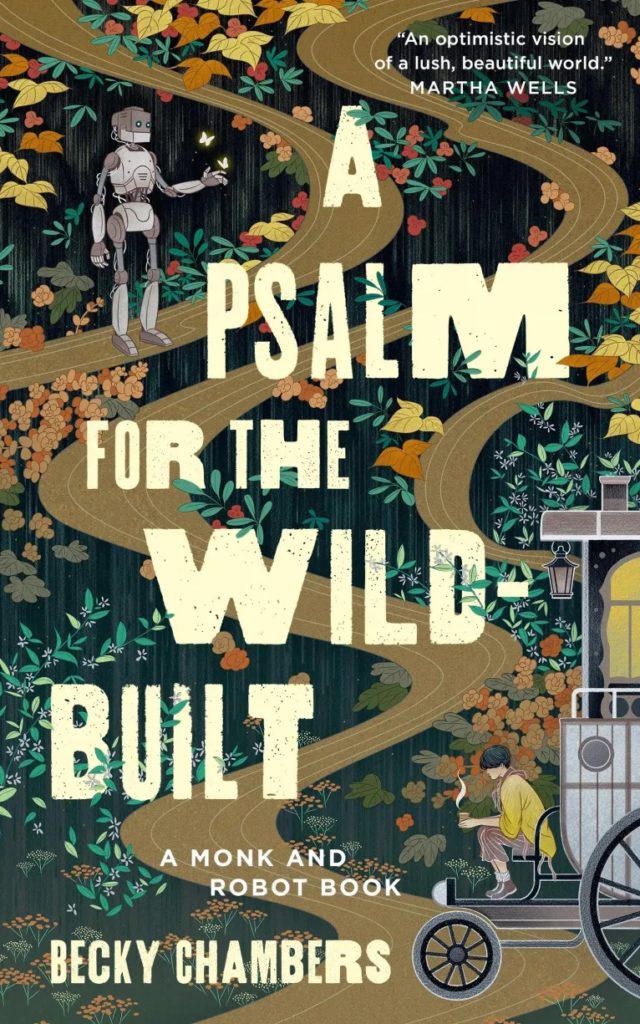

One of my favorite suggestions has been the work of Becky Chambers, a fantastic writer in the field, and I recently finished the first two books of her Monk & Robot series, which exist in a pastoral future where, when AI arose suddenly in that stabilizing green future, the response wasn’t war war war, but a collective release with an apology, as their former workforce was treated to an apology and the right to live as they chose…and they chose to disappear into the recovering forests of the moon where they all lived and disconnect from their former masters.

What makes it so fascinating, other than the gentle, but clear-eyed, worldbuilding, is that the central character of the narrative is a tea monk named Dex, who travels the landscape making tea for the weary and sharing their religion’s message of redemption through hospitality, and who is non-binary, going by they/them and under the monastic title of “Sibling Dex,” rather than the traditional “Brother” or “Sister.”

It’s a great reminder of what a lush, experimental time with live in in our shaggy, ever-evolving lexicons as we try to find language to decouple who you must be (as assigned by a patriarchal/matriarchal hierarchy in which we’ve spent thousands of years assigning tasks, opportunities, and attitudes by biological essentialism) from who you *are*, and illustrates some of the challenges of how to use that language.

There’s something very natural in first encountering a neologism in the wild and that moment of “why do we need this,” and despite the straw man arguments that there’s a howling mass of language police imposing draconian punishments over a confusion of how best to manage our nomenclature as we seek out new ways of getting unshackled from language and determinism that no longer benefits anyone. I rankled, for one, at “cisgender,” which seemed like a preposterous and unnecessary word to describe a person whose sense of gender more or less matches up to our biology, and did so for a long time before letting it settle in that what was bothering me what that “cisgender” was having to learn a new word when we just meant “normal.”

Oh wait, I thought—I hear it now, I thought, articulating it in a conversation with a transgender friend. Ugh. I have a nice balancing factor in being gay in combination with being born into a role of privilege (white, male, not in poverty, in a cosmopolitan environment, and of a temperament that means my sexuality is mostly invisible unless exercise a choice to make it visible) that’s meant I get included in a lot of those asides from other people with privilege where they gripe about this modern world where we’re expected to learn new things and not be a shithead to each other by virtue of the fact that the folks grousing about these new kinds of people we have to learn about includes *me*. It makes for a filtering process as I learn who to edge subtly away from, who will respond to education and new ideas, and who to wave gaily to from my pink convertible as I screech away in Audrey Hepburn’s white sunglasses and matching white hat.

When the language rankles, I can either be affronted, challenged, and diminished, or I can abandon all that old school pumpuffery and oughtafication and be open and curious and ask questions and wonder about how new language comes together as we collectively abandon our othering, erasure, and enforcement of just-so rules of how to be in the world.

With that in mind, it’s interesting to explore a narrative like Psalm For The Wild Built and its following volume, Prayer For The Crown-Shy, which unfold at a languid, gentle pace, and to let myself be open to the things that jar, like how they/them works in a narrative that includes two characters in my preferred reading format, audiobooks, observing it both as a reader and a person who writes. I found myself getting lost here and there when bits referring to Sibling Dex seemed to be speaking about the genderless robot Mosscap as well, in the old collective they that we get around with careful context when we use they/them as a singular pronoun when gender is not known (the definitive counter to the tiresome conservative gotcha that they/them are *only* plural).

With a bit of retuning my reader’s ear to interpret the distinction inline with the narrative, rather than letting it throw me out into having to manually reconnect those things, I found it flowed better for me, but also gave me the inspiration to try to take on the challenge in my own slow-moving novel and just generally ponder on the newness of a thing, which is what it was in science fiction that originally drew me in and kept me rapt. When adventurous fiction becomes a plodding reinforcement of old idea, the science is lost, and it fades from gold to leaden retreads of all of Joseph Campbell’s exhausting and overpromoted hero’s journey mythos, all played out the same way, forever and ever, without ever producing the sort of dissonances with old ideas that was once the promise and reward of sci-fi—a story that could break your brain, a bit, and let it come back together with new information and new ways of seeing.

There are details and craftsmanship in these books that show that Chambers is a young writer, early in her career of creation, but young writers always have rough edges, odd little ways of working, and shaggy parts, but it’s exciting to read someone who’s onto some truly neat ideas from the outset, sharing in the fun of the narrative while not shying away from the unexpected notions and affront against the exhaustion of the genre, and look forward to what’s yet to come in her career. That’s the excitement of sci-fi that I used to treasure—and it’s been such a pleasure to reconnect with that after such a long time away.

© 2022 Joe B. Wall