On my shelf, I have a book.

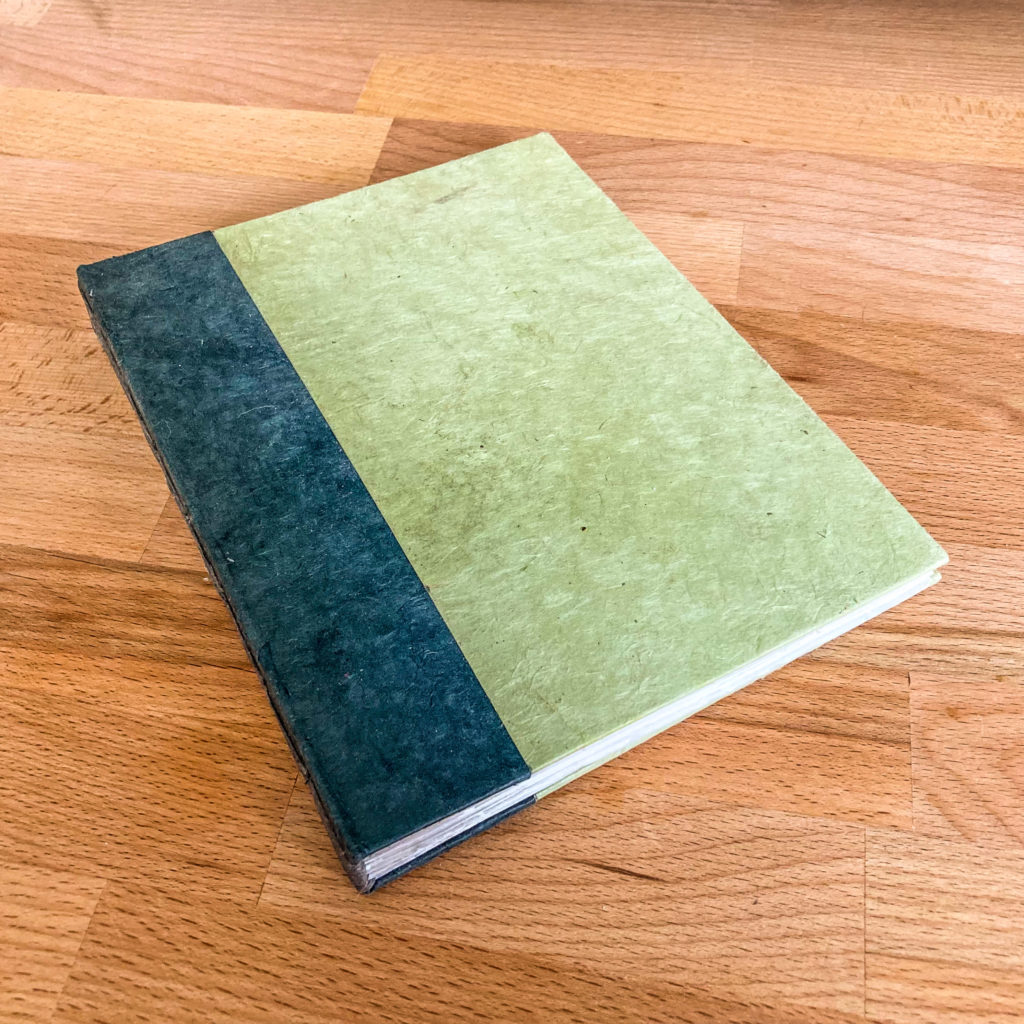

It is a handmade book that I made myself in a workshop hosted by a friend, and it is not a great book, by any means, though, of the two handmade books I have made in my life, it is far better than one I attempted in a class thirty-five or so years prior, when patience and attention to detail were less important for me.

It looks like a book, and feels, in the hand, like a book.

It sits on a table more like a wedge than the lovely foursquare block of materials that a better book would be; the edge binding being a little wider than the number of bound sections of papers, called “signatures,” would justify, but it looks and feels like it has some of the portent of a book, and carries some of the magical feeling a book carries for those who have a visceral sense of the old Arabic proverb that “a book is like a garden carried in the pocket.”

I made it and it sat and rested and waited for what I thought would be the perfect first idea to add to it.

The trouble with portent is that it creates doubt.

But one day, I decided, when I was in one of those cloudy moods where I felt like something was wrong, but I couldn’t identify either what the something or the wrong was, to start writing.

On the first morning, I woke up, rubbed the night out of my eyes, and carefully copied the first chapter of the Taoist book, the Tao Te Ching, onto the fifth page of my book using a fountain pen that I felt conveyed a sense of import to the process. Then, I made a cup of tea and enjoyed a sense of beginning, and of accomplishment.

On the next morning, I woke up, rubbed the night out of my eyes, and felt like my previous penmanship was poor and that I hadn’t properly incorporated the sense of the moment with my handwriting, and I pondered cutting out that first page with a razor blade to start over, but didn’t, for reasons of discipline or some understanding of history that was more clear to me at the age I was when starting out.

I carefully copied the second chapter of the Tao Te Ching into my book with the same pen with a sense of import, after which I made a cup of tea and enjoyed a sense of continuation and contentment.

I did the same the next day, and the next after that, eventually completing the task of transcribing one of the eighty-one chapters of the book on the morning of the eighty-first day, after which I made a cup of tea, fanned through the book, and enjoyed a sense of having started a project, persevered, and reached the inevitable ending.

My handwriting varies throughout. Some days, it’s tight and meticulous, as regular and uniform as I could make it, and others, it’s loose and rangy and rushed, because I’d almost forgotten my task until later in the morning, or because I wasn’t feeling it that day and just wanted to be done.

I’d stopped using only the fountain pen, sometimes because I’d misplaced it and sometimes as rebellion against my need for repetition and the surety of following the same paths over and over. When I made a mistake, I sat with a moment of insecurity and a razor blade, knowing how easily I could excise that day from the record and start over, but I resisted my temptation to do so. Sometimes, I would artfully correct errors with added ink, and sometimes I would just cross things out.

I shelved the book and there it was, hand-stitched binding on display like a museum exhibit of my history.

At some point, I was reminded of a quote by Colin Chapman, the architect of Lotus sports cars, who held the maxim “simplify, then add lightness,” and it was a fitting notion, so I added it to my book. I added quotes by Fred Rogers and Ursula Le Guin and bits from the Bible and Rumi. It occurred to me, too, that if I pasted in things here and there along the way, it would eventually level out the book so that it would lie flat on a table like the lovely foursquare block of materials that a better book would be, and that thought made me feel curiously settled and comfortable, even though I have yet to paste anything in there.

When I die, the book may be found in my things and recognized by someone as a sacred object once loved by a person, and taken up for the residual energy left when someone who’s no longer around leaves behind things that were rare and valuable to them for reasons other than the intrinsic value of the thing as a material object in the world. For a time, it will carry that energy, the slight sense of fizzy carbonation in the air like the happy aftermath of a beloved song that’s just ended, but eventually someone will be picking through a stack of books, sorting out what’s worth keeping and what isn’t, and it’ll just be a notebook full of scrawled notes important to someone they never knew.

They may see that, of all the notes and quotes and copied wisdom in the book, only one sentence is written in pencil, erasable and subject to being worn away just from the process of opening and closing the book over decades, and smile at the bit of ironic humor I enjoyed as I changed my writing implement for that line and considered, just as a joke told to myself, writing it and then erasing it incompletely, but they probably will miss that in the chaos of clearing out an estate or sorting through boxes of unwanted books donated to somewhere that might take them.

It is not impermanence that makes us suffer. What makes us suffer is wanting things to be permanent when they are not.

—Thich Nhat Hanh

I think, often enough, of lines I mean to add to my book, and because it is not near, they come into my head, make a tracery of blue-grey lines in the air the way my grandmother’s menthol cigarettes would fill the room with atmospheric handwriting as she’d tell me stories in her Baltimore rowhouse kitchen, before they’d slowly drift and merge into strata and fade.

Like most books that we look to for deeper meaning, my book is full of contradictions, momentary fixations, and ideas that I breezed past at first, then circled back to revisit, adding little footnotes and ornamentation.

I haven’t added anything to the book in a while, and I look at it on the shelf and have a little pang of guilt, as though I’m neglecting a living thing, which it, of course, isn’t…not really. It is a handmade book I made myself in a workshop hosted by a friend, filling up with things I’ve read or heard somewhere, bound into a volume that is like everything around me—finite and enclosed by constraints that have been defined largely by what’s happened after its construction, as resistant to a satisfying or informative summation as real stories are, and it’s no different from anything else in that it, too, might just s t o p

©2021 Joe Belknap Wall